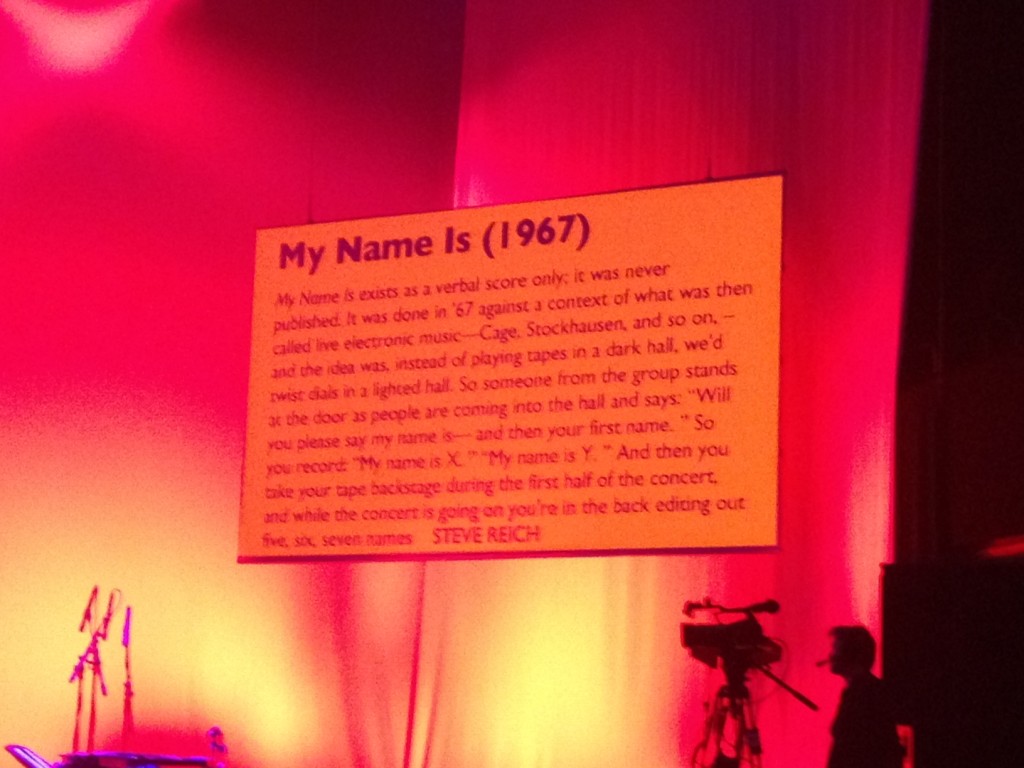

The second part of my Steve Reich odyssey takes place five days later in Glasgow. He is here for one of the Royal Concert Hall’s UNESCO Inspiring Encounters, but first there is time for a late addition to the programme. My Name Is… (1967) several members of the audience say “My name is” and their first name into a microphone.

Ensemble member Joby Burgess demonstrates how far technology has come since the work was conceived by immediately converting the sampled speech into a version of a piece that used to have to be meticulously pieced together from spliced tape. The names dissolve into a wormhole of repetition, words become noises, losing then regaining their sense.

Steve Reich warms to this theme and talks about how technology has caught up with his ideas. Dead pan, he talks confidently and assuredly about his own process. Clearly from a “classical” background, it’s interesting to hear a contemporary take on the art of composing from someone so clearly aware of his place in the musical lineage. Reich is a good talker, a harsh self-critic and disarmingly human for someone who takes their work so seriously.

He offers the invitation to the listener to get lost in the web of counterpoint. His phased work is all about patterns of rhythm, small variations make the sound ambiguous and the ear reassembles the patterns in different ways. There is some relationship to meditation, but he refuses to simplify his ideas to suit preconceived notions.

To a rock listener’s ear, it is a leap to contextualise this music without it being the soundtrack to a film. The grammar of performance is so different. Drumming, an epic piece involving tuned bongos, marimbas, glockenspiels, a piccolo and two female voices, is performed by The Colin Currie Group.

The resonance of the rhythms is such that I find my ringing ears have started to fill in the sound of instruments that aren’t actually being played. I swear I can hear horns. The intensity of the piece is a truly transformative experience in a way that rock performances have the potential to be, but so rarely are.

If you get the chance to see it, the BBC series The Sound And The Fury is a great introduction to 20th Century composers. I’m currently working my way (slowly) through Alex Ross’s epic history of 20th Century music, The Rest Is Noise, which I’d also heartily recommend.