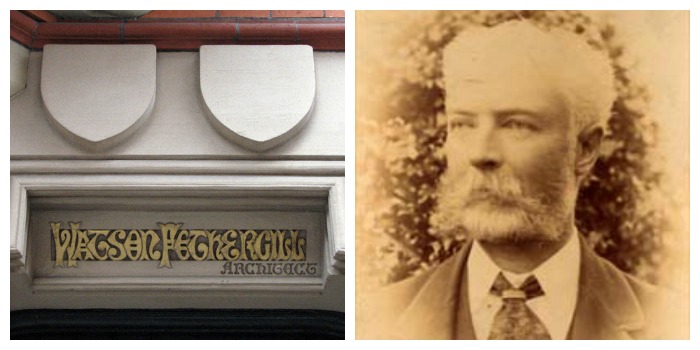

Yesterday I ventured to the other side of Trent Bridge for a talk at West Bridgford library. The topic was local architect Watson Fothergill, whose characteristic Victorian Gothic buildings can be found around Nottingham. I am particularly interested in his office building (pictured above), which can be found in Hockley on George Street. I’m hoping to include it as a stop on a tour of the area that I’m slowly working on. Fothergill was born very near where I went to school, so I was intrigued to find out more.

The talk was given by Darren Turner, himself an architect, who has taken on the task of cataloging Fothergill’s buildings. He’s even published a book, filled with sketches and as much detail as any local researcher could wish for, about the buildings that are still standing and those that have over the years been demolished.

Fothergill Watson was born in 1841 in Mansfield. His work dates from 1863 to around 1912 and in that time he mainly worked in and around Nottingham. In 1892 he switched his name around by deed poll, in order to carry on his mother’s family name (although it was to no avail as his own children didn’t produce any decedents of their own.) It seems he received a large inheritance from his father in law, one of the founding partners in Mansfield Brewery, and being comfortably off never saw the need to venture much beyond the county boundaries. Fothergill was well connected locally with a half-brother on the Mansfield Improvements Commission and the influential Brunts’ Charity, which lead to several building projects.

Several of Fothergill’s buildings in Nottingham have a distinctive look. Made of red brick with a striped pattern of blue, they also often have turrets, timber eaves and stone carvings. Anyone who has visited the centre of Nottingham is likely to have seen his Queens Chambers on the corner of Long Row and Queen Street, or the Nottingham and Notts Bank building on Thurland Street. You might also have passed the former Daily Express Offices on Parliament Street.

His office on George Street, built as a “shop window” for his work after he was forced to move from Clinton Street by the arrival of the railway, is one of the hidden gems of Nottingham. I only found it recently while exploring the “Creative Quarter”, it was recently up for sale and there was talk that it was bought by some Fothergill enthusiasts with a view to renovating it as a museum.

The exterior is a homage to his mentors with busts of the architects Augustus Pugin, George Street, George Gilbert Scott , William Burges and Richard Norman Shaw honoured in stone. There are terracotta panels depicting architecture through the ages and masons at work on a gothic cathedral. The individuality of the design makes this a distinctive building for the 1890s, full of idiosyncratic details. This office, like many of Fothergill’s buildings, shows the influence of his travels in Bavaria and Venice, with details from European Gothic given a particular Victorian twist.

Although Fothergill is no Gaudi or Mackintosh in terms of the scale or fame of his buildings, his distinctive style has left its mark on Nottingham. Some of his buildings did not survive the drive for modernism that swept through the city centre in the 1960s and 1970s. Notable losses include the Black Boy Hotel, which by the time of its demolition had become “notorious” (according to my mum at least…). It was pulled down in 1970 and a large branch of Primark now occupies in the spot on Long Row where once it stood.

Darren Turner’s book goes a long way to establishing a full list of extant buildings as well as clarifying the provenance of some which have been mis-identified in the past and I look forward to discovering more of them on my walks through the city.