I’ve started a new venture, guided walks around the buildings of architect Watson Fothergill in Nottingham. I’ve conducted two walks so far, and I am planning more events soon. At the moment the details are over on WatsonFothergillWalk.com

Writer, Researcher, Tour Guide

I’ve started a new venture, guided walks around the buildings of architect Watson Fothergill in Nottingham. I’ve conducted two walks so far, and I am planning more events soon. At the moment the details are over on WatsonFothergillWalk.com

These days Nottingham has thriving art and music scenes, independent shops, decent coffee and even the first independent UK book shop to be opened this century, Five Leaves Books.

Working in association with Walking Heads, my colleagues based in Glasgow, we realised that these two great post-industrial cities have much in common as they re-invent themselves for the challenges of the 21st century.

The tour looks at the history of the area of Nottingham now designated as The Creative Quarter and meets some of the people who work in the varied creative industries in the area.

The tour takes in The Lace Market, Hockley and Sneinton Market including New College Nottingham, where students of art and design learn their trade, and established independent craft practitioner Debbie Bryan who takes inspiration from the Nottingham’s lace heritage. There is art from leading gallery Nottingham Contemporary and curator Jennie Syson; Find hidden gems in unexpected places, like a Morris & Co window in the largest pub in town. Dig down to the caves and secret passageways of The Galleries of Justice, one of Nottingham’s top tourist attractions and discover some remarkable stories from the history of St Mary’s, Nottingham’s oldest and largest church and find out how it is used as a creative venue today; Learn about local cultural magazine Left Lion, who bring Nottingham musicians, actors and writers into the limelight. Explore the regenerated Sneinton Market and the thriving gallery scene around St Ann’s and Sneinton.

Celebrate 25 years of Nottingham media and cinema, at Broadway and find out about the “playable building” that is home to the National Videogames Arcade. Finally step through the gate of the transformed Cobden Chambers to find independent businesses getting established with the help of Creative Quarter, not to mention tales from Dawn of The Unread, where Nottingham’s literary past is woven with the many layered history of the textile and lace industries which built the grand architecture of The Lace Market…

The tour is narrated by Nottinghamshire-born Dorothy Atkinson, who you may know from her work in films made by Mike Leigh… we recorded at JT Soar, a nearby studio & music venue which used to be a Fruit and Veg warehouse.

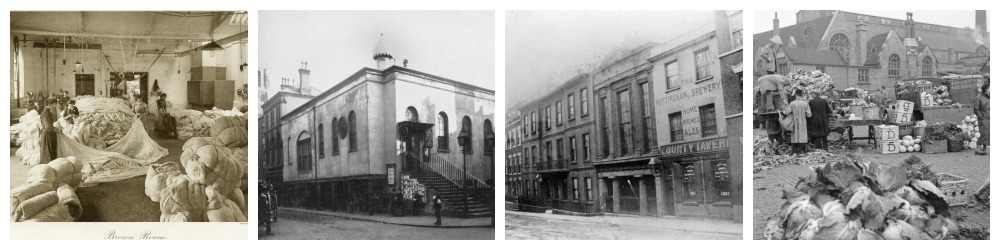

The tour features archive photos from Picture The Past, who have kindly let me use images as a pilot scheme.

The tour is available to download free on Guidigo (which is also free) on iPhones, iPads and Android devices.

A trip to London requires planning, an ample budget and a lot of friendly sofas to sleep on. All these elements came together last week and I went in search of some refreshing cultural adventures.

For the last several months I’ve been working on something in Nottingham (that I hope to be able to tell you about soon). The project has renewed my interest in architectural history (see my earlier blog on Watson Fothergill) and sent me off in several directions.

Trying to track down the provenance of a stained glass window attributed to William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, but produced after both their deaths, led me to the local library and Fiona McCarthy‘s hefty biographies.

Having enjoyed both books, particularly William Morris: A Life for Our Time, I resolved to see some of their art and in the case of Morris, the house he built on the outskirts of London.

I had a wish list of things I wanted to see while I was in London and I managed to pull quite a few of them in along with a few other pleasant surprises along the way.

First, The Wellcome Collection, within striking distance of Kings Cross/ St Pancras and with a friendly cloakroom to relieve me of my suitcase for a few hours. I queued for a while to be admitted to a room full of coloured mist, a reboot for the senses – an art installation, States of Mind, a prelude to a larger exhibition about “consciousness” due to start next year.

With time to wander, I fulfilled a long held ambition to find the grave stone of Mary Wollstonecraft in Old St Pancras Church Yard. This is also home to the Soane monument (the shape of which inspired the design of the telephone box – a fact I learned on my last visit to London when, unable to get into an overbooked exhibition at the British Library, I visited the unexpected delight of Sir John Soane’s Museum, of whom more later). Loose ends were starting to be tied up, it was Fiona McCarthy’s insightful biography of Lord Byron that had piqued my interest in Shelley and Mary who were known to tryst at her mother’s grave…

The following day I had planned to visit the V&A, whose tearooms alone are a treasure trove of Morris & Co designs, but on the way there I got distracted. I’d spotted a striking poster for an exhibition at RIBA – on Palladian architecture. Having never visited their Portland Place HQ before, I was impressed by the building and even more taken with the clean, well arranged exhibition of drawings and models.

By the time I reached Kensington, the full armageddon of half-term week in museum-land had hit and I abandoned hopes of the V&A in favour of retaining a shred of sanity. Towing a case around London limits what you can do and I fell back on one of my favourite places, which just happens to have a spacious free cloakroom, The National Portrait Gallery. I seemed to be the only person who’d read the small print and found the app to accompany Simon Schama’s Face of Britain exhibition and I let his distinctive tones guide me… The dots continued to be joined – a portrait of William Morris’s wife Jane appeared in the ‘Love’ section.

The next day, relieved of the burden of my case, I decided to pull in another visit I’d been thinking about for a long time. The Banqueting House, the last vestige of Whitehall Palace – and Britain’s first Palladian building. An exercise in well guided tourism – with not only a comprehensive audio guide, but also an eager and entertaining steward keen to talk the handful of visitors through the history of this hidden gem. Currently undergoing restoration on the outside, the stone work was originally refaced by Sir John Soane (and the connections on this trip just keep mounting up).

I then took a train out to Bexleyheath and found The Red House, which William Morris and his wife had built and lived in between 1860 and 1865. Despite being there for only a short time, it was pivotal in the creation of his design business, eventually called Morris & Co and its very walls tell stories of the decorating parties held there with artists, poets and other luminaries of the period all contributing to the patterns and schemes which the National Trust are still discovering hidden under the modern wallpaper. The purpose-built house has a studio space to make even the most casual artist jealous, full of space and light. It was easy to imagine the “Topsy” of McCarthy’s biography in these rooms. I picked a windfall from the orchard and put an oak leaf in my pocket, hoping that some of the inspiration would rub off.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who was often at The Red House, was fascinated by wombats and kept them as pets. He often drew caricatures of his friend (and rival for the affections of Mrs Morris) where the roly poly animal stands in for the artist. He even named one of his wombats Topsy. The National Trust have instigated a Wombat Hunt for The Red House’s younger visitors. Cuddly marsupials abound in each room…

A conversation over the Wallpaper pattern books in the Morris children’s old bedroom prompted me to investigate the William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow and the next day I headed out to the furthest stop on the Victoria line to find a rather wonderful Georgian Mansion where Morris lived for part of his childhood.

It has been refurbished as a gallery with space for contemporary exhibitions as well as an archive of objects from his life and work. My favourite items being his extra large cup and saucer and the leather satchel he took around the country when engaged in socialist lectures later in his life.

Above all, Morris seems to have been someone who possessed great enthusiasms, about poetry, art, fairness and fellowship. The gallery does a great job of bringing these to life. The accompanying exhibition documenting Bob & Roberta Smith’s campaign to save arts education for children chimed well with the themes of Morris’s own life and the continuing relevance of his ideas.

I headed back on the Victoria line to Pimlico and Tate Britain, to wallow in the room full of paintings by Rosetti and Burne-Jones.

The evening ended up with a visit to an old friend in Deptford – where there are so many stories and secret places it will need a blog all of its own…

Saturday began with a trip to Borough Market, a walk along the Thames (pausing to look in at the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall and taking a ride in the singing lift at the Royal Festival Hall). Tea in the Crypt at St Martin’s In the Field (another Palladian building), then using up the last of my energy for one more exhibition – Goya: The Portraits at the National Gallery, which was crowded and expensive but still impressive.

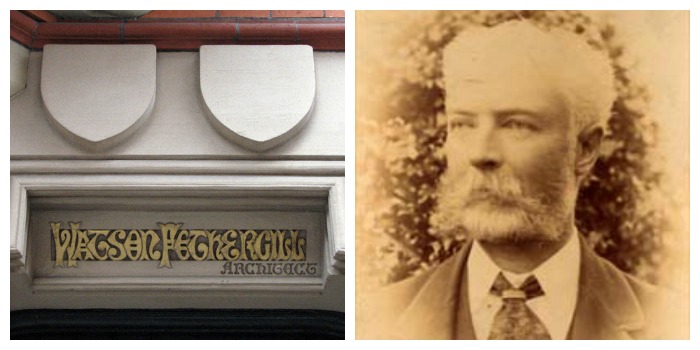

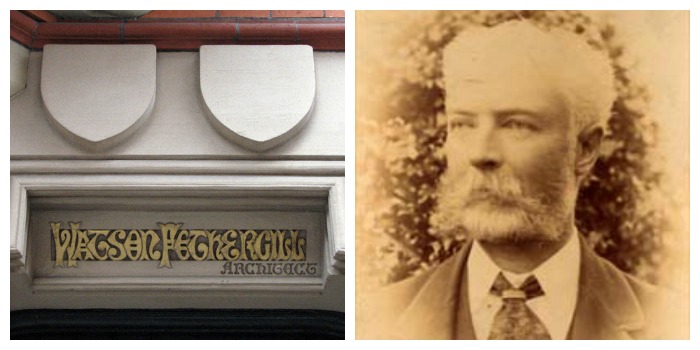

Yesterday I ventured to the other side of Trent Bridge for a talk at West Bridgford library. The topic was local architect Watson Fothergill, whose characteristic Victorian Gothic buildings can be found around Nottingham. I am particularly interested in his office building (pictured above), which can be found in Hockley on George Street. I’m hoping to include it as a stop on a tour of the area that I’m slowly working on. Fothergill was born very near where I went to school, so I was intrigued to find out more.

The talk was given by Darren Turner, himself an architect, who has taken on the task of cataloging Fothergill’s buildings. He’s even published a book, filled with sketches and as much detail as any local researcher could wish for, about the buildings that are still standing and those that have over the years been demolished.

Fothergill Watson was born in 1841 in Mansfield. His work dates from 1863 to around 1912 and in that time he mainly worked in and around Nottingham. In 1892 he switched his name around by deed poll, in order to carry on his mother’s family name (although it was to no avail as his own children didn’t produce any decedents of their own.) It seems he received a large inheritance from his father in law, one of the founding partners in Mansfield Brewery, and being comfortably off never saw the need to venture much beyond the county boundaries. Fothergill was well connected locally with a half-brother on the Mansfield Improvements Commission and the influential Brunts’ Charity, which lead to several building projects.

Several of Fothergill’s buildings in Nottingham have a distinctive look. Made of red brick with a striped pattern of blue, they also often have turrets, timber eaves and stone carvings. Anyone who has visited the centre of Nottingham is likely to have seen his Queens Chambers on the corner of Long Row and Queen Street, or the Nottingham and Notts Bank building on Thurland Street. You might also have passed the former Daily Express Offices on Parliament Street.

His office on George Street, built as a “shop window” for his work after he was forced to move from Clinton Street by the arrival of the railway, is one of the hidden gems of Nottingham. I only found it recently while exploring the “Creative Quarter”, it was recently up for sale and there was talk that it was bought by some Fothergill enthusiasts with a view to renovating it as a museum.

The exterior is a homage to his mentors with busts of the architects Augustus Pugin, George Street, George Gilbert Scott , William Burges and Richard Norman Shaw honoured in stone. There are terracotta panels depicting architecture through the ages and masons at work on a gothic cathedral. The individuality of the design makes this a distinctive building for the 1890s, full of idiosyncratic details. This office, like many of Fothergill’s buildings, shows the influence of his travels in Bavaria and Venice, with details from European Gothic given a particular Victorian twist.

Although Fothergill is no Gaudi or Mackintosh in terms of the scale or fame of his buildings, his distinctive style has left its mark on Nottingham. Some of his buildings did not survive the drive for modernism that swept through the city centre in the 1960s and 1970s. Notable losses include the Black Boy Hotel, which by the time of its demolition had become “notorious” (according to my mum at least…). It was pulled down in 1970 and a large branch of Primark now occupies in the spot on Long Row where once it stood.

Darren Turner’s book goes a long way to establishing a full list of extant buildings as well as clarifying the provenance of some which have been mis-identified in the past and I look forward to discovering more of them on my walks through the city.